Biography with pictures

While preparing this book, the necessity for writing a factual biography had arisen. However, when *Ági Bakonyvári, the editor of the book, was ready with the work, and I first went through reading it, what occured to me was how little do the facts comply with the truly important and determining influences, relationships, experiences in one’s life. I have attempted to fill in this missing part with the present writing.

My first substantial childhood memories go back to Tatabánya. Great wanderings, hanging around in bands in the world of sulphate- steaming,barren volcanoes, crusty surfaced potholes of mud, rusting mine vagons and altrenately bomb craters interwoven with gossamer, scrubby shrubberies, and the forgotten old forests.

Freedom unsurpassable. The Turul, the Shiny- and the Oldlake of Tata, the thermal water of Bánhida Centrálé, as well as the incredible fine dust from the cement factory enveloping everything in grey, also the awkward concrete jugs of the power station; all of which have left unerasable marks in me.

The bitter memory of this time is the divorce of my parents. I loved them both equally.It posed an irresolvable dilemma for me that I had to choose betweenthe two of them. Today I can understand them and sympathise with them, yet, probably it was due to this psychic trauma and the vulnarability of the scars that I was drawn later on to art.

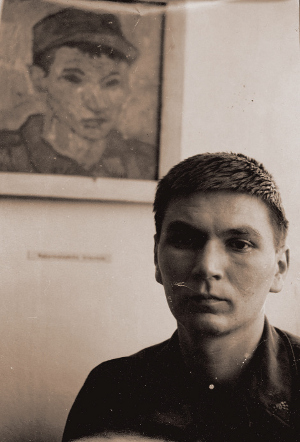

Planning to be an architect I felt the need to develop my drawing abilities too. The pleasure taken in comprehending the tasks, solving them, and acquiring the basic knowledge aspired me, forgetting architecture, to go for painting. I was admitted, at the second attempt, as a day student to the School of Fine Arts, having worked in the meantime as a layman at the Kelenföld Thermo Power Station and done a preparotary evening course in arts.

Although my entrance examination was successful, my prelearnings at the course were only sufficient for hiding the gaps and covering my lack of basic knowledge in the fine arts. I was seventeen when I first visited the National Gallery. I felt overwhelmed by the works of the contemporary painters. However, I had not known any of them.

* Demonstrator: A personselected from the students.

At the School of Fine Arts who helps the Master with his/her work. (Employing models, getting items needed, object for still life. I kept going back to the pictures that I liked, and was memorising the names: Márffy, Gulácsy, Tornyai…

My tutor at the College was Aurél Bernáth. I found him overrefined, kind of aristocratic for a painter, but the sensitivity he treated us with, and the enormous culture that shone through every single word of his, made me overcome my misgivings. Later on, getting more acquainted with his mode of depicting I also found elements in his work that were close to me. I have been his demonstrator* for years, which has provided me with some honorarium as well, and which together with the financial support from my father has created consolidated economic circumstances.

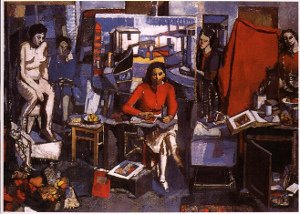

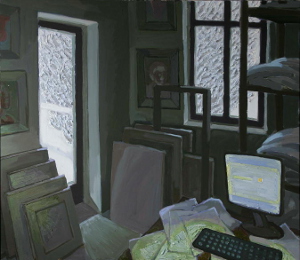

The tutor could help a lot, but we learned the most from one another. My greatest learning at the School was my chance of getting acquainted with Béla Grúber’s work, most importantly with his picture titled ‘Atelier’, displayed in the library. I recognised, at the first sight, that I had to do with a masterpiece. Later on, bit by bit, I came to understand the work method of the painter, his mode of thinking, apprehended the intimate relationship that existed between him and the theme, his objects, his characters. I was enthralled by the free use of paint, the underlying, inherent possibilities of the faculty. I made an atelier-study myself, as a way to define my relationship to the atelier, the precursors and the art of painting itself.

Already, at this studying period of my life I felt that selfknowledge was the most important element in getting further. What caused the biggest problem in my work was that my outburst of intuitive expression and my attempts of conformation dictated by the mind, had duly kept opposing one another. I feel, I have to elaborate the above two statements: ‘intuitive expression’ and ‘attempts of conformation’. Perhaps, I should begin with the time when doing study paintings I gradually came to see the role of ‘inspiring experience’. I realised that the world, people, faces:’ the sight’ happen to be, sometimes, at exceptional moments of grace, in complete harmony with me. In a way, as if it was the projection of my feelings, moods. This feeling of identificating was so overwhelming that it forced me to get hold of the thing, mould it into a picture. In such moments, painting became a spontanous, natural flow, a perfect print of my billowing and hardly describable feelings.

It was a highly charged, two-folded experience; that of perception and that of painting. In between the two, by capturing the identical matters, endless opportunities were opening up enabling deeper explorations in myself. As a result of all these, ‘sights envisioned within the sight’ gained importance, which visions could only be attained through the attaining of the sight itself; through merging in it, and exploring it. Hence, my intuitive expression was guiding me towards close depicting.

Now, some words about the ‘attempts of conformation’. I was a young man, full of faith and determination in the prospect; that living in a certain age, projecting my experiences, comprehending the different streams of the century; among them finding my own place: I myself would become a ‘modern’ painter. The identificating and the projecting of my experiences were going on the right track, while comprehending the streams of the age was primarily an intellectual task. When analysing the different ‘-isms’, tendencies, streams, taking account of their potentialities and shortcomings

I often arrived at the conclusion that in 20th-century art ‘sight’ and its subsequent ‘experience’ play a subsidary role, and are almost considered degrading characteristics of the ‘old-fashioned’ artist. In my opinion, another significant contradiction was the fact that in our age of accelerated interchange of streams the most popular seemed to be the one that produced a shock-effect; presented the unexpected, thoughts without preliminary events. Doing this, in controversion to the best artworks of the past (several) thousands of years which, in my opinion, share elementarial expression as their mutual and main characteristic. (By the term ‘elementarial expression’ I mean the overwhelming effect of the artwork that purges all misgivings, and which, by way of its quality, convinces of its righteousness.)

Based on all these, I thought to put aside my experimentings on conformation and concentrate primarily on self-exploration and authentic expression. In this agony of acquiring selfknowledge, getting acquainted with my friends meant a tremendous help.

The evaluation of their agony, successes, failures have, in a relatively objective manner, revealed the same process going on within me.

Among my friends, firstly, I would like to mention Károly Lengyel. We started off together from Miskolc. His drawing knowledge and his technical abilities have already impressed me while doing our preparatory studies. At the School of Fine Arts, we were course-, and room-mates, He was a hard working man with extreme devotion to the craft, at all times a wonderful diametrical opposite to my carelessness, and superficial solutions in work. The distillation of reality through crystallization and the abstract idea above that were simultaneously present in his work. I have not stopped learning from him up to the present day.

My other friend from whom I have learned a lot is Endre Hegedűs. A figure of contradictions, resolute in his work with no excuse, at the same time, a man being tortured by doubts. Standing in front of his empty canvas almost paralysed by the notion of the multitude of arising possibilities and the barrier of his own abilities. The expressive projection of this tension in his work has filled me with envy, many a time; just as his inner struggle has done, with sympathy. Affected by this, I have tried to restrain the full swing of my work, so that my constant drive for action should not lead me to bypass any contradictions.

Apart from studying the works of colleagues and friends, extraordinary lessons were learned from studying the reproductions of the great masters. At the time, we could not think of travelling, visiting museums abroad. Browsing the books, unlimited possibilities have been reaveled in the art of painting ; my attraction or misgivings towards them serving new information about my own inclinations or possible route. The huge amount of possibilities urged me to work even harder.The daily 8-10 hour-work resulted into the fact that life in the workshop, the studies and the experiences there, did no longer leave me satiated. I had the notion that only individual life can create individual art. I must leave this protected world of the workshop, so that the impact of the yet unknown real life would mould me, and my work.I handed in my request of taking a year off from College to the directory of studies. Soon, a notice came from the Army saying that since I had left school I would be taken for my national service in the autumn.

Here, my cowardice has intervened. I hastily withdrew my request ofpostponing my studies, and returned to the workshop. I have to write about one more friend, so that to make the continuation of the story clear: T ibor Eisenmayer.

On leave from the Army

László Tenk: The Magical Stag

He was a most peculiar being. Energy, obsessed determination, frantic talent, uncontrollable temper. Sharp criticism, merciless self- analysis were of his characteristics. The age in which we lived had only fed our discontentment and our opposition to the ‘orderly’ majority. My cowardice regarding my taking a year off had only further upset my inner peace and relationship with the School. As I was a restless, with some exaggeration one could say, reckless, at times a vehement fellow; all these contributed, after several disciplinary cases, – following our being involved in a fight, – into our dismissal from College.

The bizarre twist or the justice of fate is that at this time, after half a year of being expelled from school, I was taken for my two-year national service, which – looking back on it – was the time of my growing up. This hard, hostile milieu to art had both tried my capacity of conformation and tolerance. In spite of this, I got enpowered in matters that were important to me. Instead of outbursts of enthusiasm; persistence, endurance and sacrifices became essential. By now, I knew what I wanted, and also that I would carry them through against all odds.

1968 Czechoslovakia.I was amongst the enmarching soldiers. It was a shocking feeling of being used in the supression of a revolution. The possibility that I might shoot at demonstrating students triggered off a series of romantic envisages (searching for ways of escaping, desertion, joining the opposite forces). Fortunately, none of these had to be realised. The crashing of our own revolution was still a fresh memory in the minds. The ‘big brother’: the same. The lesson learned from the events, the reliance upon one another of the neighbouring countries, their similar fate. It was good to see, though, the steadfast, symphatetic way of conduct from the majority of the Hungarian soldiers. In the wake of the first befriendings – within a few months – they withdrew us from the country.

After my national service, Károly Lengyel gave me a home in a one time hot- house used for growing plants, now, serving as an atelier.

Once again, I was enabled to continue searching (also as a painter) for my path. I imagined expression exclusively aided by the depiction of human figures. The period of searching my way are marked by portraits, figures, or compositions of figures. Dislocations only took place between the modes of close or more abstract depicting. My experimentings directed on the former mode were focused on bringing the subconscious matter to the surface, by way of liberating the senses.

I had this idea that the smallest unit of direct performance is one stroke of the paintbrush, which (the same way as graphology) reads legibly everything about me, as the underlying, second layer of the content. Opposite direction to this was to reveal, or rather, attempt to reveal, the more universal, the more abstarct connections beyond the impulses of the sight. To capture the nature and the order of the colours, the movement and the light.

I have attempted to compose philosophical ideas, too. At first, I used light as a force breaking up forms. Then, as one that enables free ensembling; a force with an organising power which casts beyond the eventuality of the sight. As my need for depicting the abstract was decreasing, so was the role of light gaining prevalence in the sight itself.

Light, as an increasingly effective carrier of feelings, moods was gradually taking up a larger role. In the meantime, depicting human figures was losing its importance, while scenery, land took the lead. The marks of pictorial ‘exploration through human figures’can be seen in the first chapter, titled ‘Human Mound’.

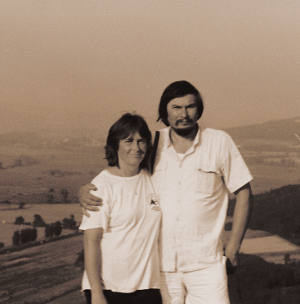

After the hot-house period, I worked at the Artists’site of Kecskemét. According to my thinking of the time a commited artist was not to marry. Regrading his/her uncertain existence, and his/her work demanding a whole person, it would have been an irresponsible action. This was the time when I first met my future wife, a married woman. Our meeting has overthrown all my clever ‘ideas’on the matter of matrinomy.We looked in each other’s eyes for a long time, falling headlong in love, and left the Artists’ site at the same dawn.

A thirty-six- year-of life together. The balance of it: three children, seven grandchildren, many-many journeys, deprivation, sorrow and joy. The chapter titled ‘Ten Gobelins’tell about our work together and the piece titled ‘The woman of the gardens’ stands to the memory of my wife.

Having a family was imposing growing responsibilities, therefore, I applied for an atelier-home in Debrecen. We lived for five years in Debrecen. At first, we had to struggle for getting accepeted, then for our survival.

In the meantime, at Nyírbátor, I was directing a studio for art teachers and a fine-art-circle for secondary school students. This job, apart from providing me with the opportunity of working with excellent people, also pressured me to clarify professional questions, for which I feel very grateful to them. In Debrecen, I remained a stranger. Provincial mediocrity, petty inner conflicts. I returned the key at the first opportunity, thanking the hospitality.

Kispest, a room with a kitchen, and a provisional atelier, created by pulling a wall down in my father-in-law’s house.Cosy, small townish environment, friendly people and houses. A place where I could visualize our future life.

Kispest, a room with a kitchen, and a provisional atelier, created by pulling a wall down in my father-in-law’s house.Cosy, small townish environment, friendly people and houses. A place where I could visualize our future life.

Another determining experience follows with affect on my work and life: a fantastic journey of research to Paris, Dusseldorf, Marseille.

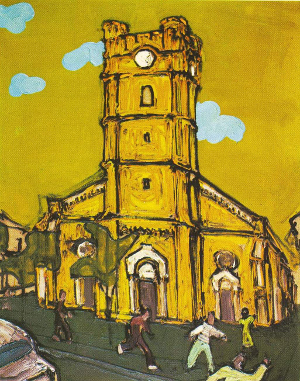

Breaking away from the familiar surrounding, travelling abroad is a great experience on its own, in addition, it was my first time to come in direct contact with the works of the great forerunners: Van Gogh, Cezanne, Matisse… Seeing them, broke down all the remaining barriers rising in front of my insofar unsteadily shaping self-expression. The inner struggle has come to a halt for a long time to come. The insofar rational approach has been swept away by the enthralling experience of free style painting. I felt, what I had always been attracted to; I must listen to the inspirations of reality, rely on my intuitions instead of conformation, I myself have to choose freedom. Intuition or sensation seemed to be the more reliable guides, even though, I had never questioned the primary role of the intellect. The great experience, the overwhelming urge for expressionand free style painting together would create the ‘performance’, at the same time, also my future style and expression. The chapter titled ‘A painter in Venice’introduces a selection of pictures which reflects the euphoria of travelling and the external way of ‘searching for a path’.

This first trip have been followed by several others, all of which were learning experiences. At the time, one month was the exact period of time that one was permitted to spend abroad. Not long enough for a world – the land, museums, townswaiting to be discovered, to get acquainted even with the fraction of it. But a lot, when one had to make order amongst the mass of impressions piled up.

After spending a hectic month in the uncertain, homecoming gave different kinds of joys. After our having a torrent of experiences in the racing world, home offered us safe shelter, the seeing of our beloved ones, the scenery, the fatherland, the language, all in all suggesting a feeling of intimate peace, steadfastness and security. As an effect of the journey, our recurring everyday scenes, moods of life have undergone a new evaluation. The recognition was perplexing: where do we rush, why do we pursue the unknown when the most expressive things, the most suitable sceneries for reflecting our feelings are lying right here, at our feet. The ‘Homecoming’ titled chapter shows a selection of these pictures at home.

Csillaghegy (Starhills) deserves a chapter on its own. After demolishing our house in Kispest, this is where we bought a castle ruin. When we started looking for a home, this was the first house we looked at. The surrounding, the square, the distance from the town and the view overlooking it, the outskirt, the region, the people who lived here have immediately made it a home for us, or rather a possibility for one. The renovation of it, the fire destroying it, the rebuilding it were trying experiences. I have been building it for the past thirty years (and still love doing it). My one time attraction to architecture, has finally gained grounds. By now, the house has become like myself. Besides, all my children, daughterand son-in-laws, grandchildren live here. It is also my home, attelier, gallery. The chapter titled ‘Jazz-calvary’ select pictures inspired by this closer environment. Perhaps, I could best compare this natural feeling of being at home – what Csillaghegy means to me – to my childhood experiences in Tatabánya.

Perhaps, it would not be without interest to present an alternative biography of mine, at this point, written at about this time. I could not add much to it even today, except for the names of one or two ‘great personalities’- that I have met since.

Our life in Csillaghegy, our getting out of town had also increased the distance from the people. It was nature that offered a suitable medium for depicting human fate, feelings, situations: the tree. I present trees, portraits of close friends, group- pictures in the chapter titled ‘Willow-country’.

Painting provided financial gains, a possibility for making a living only through the Art Gallery enterprise. I have been giving paintings there for over fifteen years.

About myself, about my work

I was born in 1943, in Nagybánya. I could continue with when, where, how I lived … ? Instead my favourite authors: Attila József, Dostoyevsky, Faulkner. In music: I favour the works of Bach, Stravinsky and Bartók, and the albums of the Beatles and Elton John. I value Bejar and Brook. The king of films: Fellini, that of sculpting: Michelangelo, that of painting: Csontváry. My art tutor was Aurél Bernáth. I think of painting as a tool for discovering the self and the world. The world is an ugly building. Muddled ideologies clash, terrifying perspectives open up. Indifference, pushing onself in front are useful characteristics; detachment – objectivity, palaver-making – healthy rages; the tortuousness of the mind – structure; the syrup – deep feeling. Nature is dying, relationships are getting reducted, we live in tree-hollows, feed on substitutions, do not get to know one another. Children grow up without parents, parents grow old without joy, the old die without compassion. This is the world where I take the stones from, so that by rebuilding it, it would become better. My stones: faces, flowers, movements, objects, streets, moods – only the binding material is different, love. While getting befriended with the accusation of anachronism, I put forward my work for consideration.

Budapest. 10th December 1979

*Dr Magdolna Supka (19-2005) art historican, completed studies on the works of the great contemporary and recent figures og the fine arts, amongst them: Vilmos Aba Novák, Lajos Szalay, Menyhért Tóth, György Kohán. I must say I was fortunate even with this. We had a tolerable life, free of significant deprivation. The paintings that occasionally show up from this period do not talk about making compromises out of financial interest, rather about the fact that I have been giving my best pictures away in return for security. Most of the pictures handed in there were still lifes. Their themes were usually flowers, objects, odds and ends found in the atelier. The ‘Lily and hammer’titled chapter shows some of these pictures.

A gift of life was my meeting Manna Supka. We have been friends from the eighties. I can hardly give account of the enormous help I got from her. She was the first person in my adult life who addressed my work in effect. Her perceptions, advice, criticims helped me confirm the self-expression which I had already formed. She helped me with my work, helped me to scramble out of professional pitfalls helped to set up exhibitions, helped by writing about them, and most of all, helped by believing in me. For the spectator, through her writings and openings of exhibitions, she has brought my work within comprehensible spheres. When introducing my work, I often recall her with the help of her old studies.

I was among the first curators of the newly established Common Foundation of Creative Art, following the closing down of the Art Foundation after the political changes, in 1989. We fought a heroic but a naive war for saving the artists’ funds and making them functionable. You may laugh at me, because at one time, I even became, as a mock economist, president of the Board of Directors of the Art Gallery HoldingCompany. I thought if I took part in setting assignments in the craft, follow them up, the whole of our profession would gain access to opportunities with each artist benefiting from it according to his/her abilities, talents. It was not up to me that this man-trying work did not bring the desired result.

Similar thoughts motivated the establishing of the T-art Foundation, in 1990. By this time, one could see that art would fall prey to the changes, on the short run. It also started to show that democracy and quality classification of the artists contradict one another. From common financial source only the whole lot can enjoy preference.The definition of quality, and its individual support can only be fair if it is subject to responsible judgment and if the interested, supportive forces join in action.

We have created this foundation with my wife with the view of organising these forces, supporting the artists, and establishing a permanent collection of contemporary art.

It was threatening that with the state sponsorings getting exhausted, the artists and the art itself would find themselves in a vacuum. The future of art is the creation of a selective and comprehensive audience which is ready to take on sacrifices in order to help art survive. The Collection of Contemporary Art of the Foundation was to serve to inform this shaping, particular audience of the art. Here, I must add that the items of the collection came as donations from the artists requested. There was only one criterium to the request: artistic quality. We have been looking for the possibility of the permanent exhibiting of this collection for the past decade, so far in vain. The individual and group exhibitions that we organised at home and abroad were also positive actions in building the relationship of audience and artist. And, one more anthology of published materials realised with our involvement, which also indicates what we did-, and what we do consider as quality.

The public obligations did not come in the way of my work. When I meditate upon this period, I must say that the public work made no significant influence on my work. Even though I spent a lot more time with people, the tendency of my depicting; which was leading to the slow diminishing of the human figures, against the overtaking of the scenery and land – did not revolt. This change of tendency is well reflected for comparison in the chapter titled ‘In Saint Francis’s land’,which is a selection of the pictures born out of the experiences of the most recent journeys.The ‘Path towards the light’ touches questions on faith, life and death, while the ‘Wall and gate’ presents, even to my knowledge, a series of meditative, observing pictures.

Painting itself was sometimes better sometimes worse. At times, the familiar served as inspirations, at others, the unusual. Artists’sites, and friends working there, have always given great boost to my work.

Painting itself was sometimes better sometimes worse. At times, the familiar served as inspirations, at others, the unusual. Artists’sites, and friends working there, have always given great boost to my work.

Life, unfortunately, had taken care that this flow would break from time to time. Our house burning down, was a traumatic experience, at the time. However, being a young person it was easier to overcome, what is more, it made me bring my energy in focus.

László Tenk: Atelier, winter, monitor

In 2000, another misfortune set in. Hemorhage in the brain, of the worse type. I was lucky to recover. For a period of time I was painting with my left hand, later on also my right hand regained its mobility. I tried to learn a lesson from the affliction, rationalised my disproportioned, overloaded life; returned-, or turned down several public duties. Since that, I have been using my energy in a more sensible way. Though, the illness itself poised as a disabling factor, it helped me grow in self-knowledge. No sooner did I get out of the depths, with my wife helping me, than another affliction imposed upon us. Our life together came to be jeopardized, with Zsóka’s ailment.

Five years of superhuman struggle, and the unavoidable took place. Unfortunately, I was too little to help her, as she helped me, get out of the affliction. Her illness had set me back in my work, as much for psychological as for physical reasons, for we required all our energy to withhold and endure the illness. The picture completed not long before her death is a true reflection of my psychological state at the time.

One dawn, when turning on the computer, I was struck by the contrast of the two different kinds of cold (almost rigid) light; the gravity, the robust rigidity of the objects in the instreaming light of the outer world and the rebouncing light of the new world.The sight was crowned by the timeless, plastic view of the snow-covered tree in the window..

At this lowest psychological state I was approached by my friend Flórián Kugler, with the request of realising this book.

Two years have gone by. Not once, did I feel that the tsk was outwearimg my strength. After other times, I was wondering whether anyone ought to make an albumof oeuvre at trhe age of 64. By all means, I consider to have made order omongst my picture, a positive factor. I have got over seven hunred paintings stored in my computer, together with all their datas. The biography has been completed, so has the list of exhibitions, as well as the enlistment of my awords, and literature written on me. As for the selecting, and the organising of the pictures in groups: they have revealed such, insofar hidden, connections which I hope, I will be able to make use of in the future.

László Tenk